Recognizing Medical Crisis: Diabetes

Approximately 29.1 million people or 9.3% of the U.S. population have diabetes(1). The risk for diabetes is increased among individuals who have serious mental illness (SMI)(2). Individuals with bipolar disorder or diagnoses on the schizophrenia spectrum are 2 to 3 times more likely to develop diabetes than the general population (3,4). Depression also increases the risk for diabetes (5,6). The high prevalence of diabetes in the SMI population is a result of biological, lifestyle, and environmental factors(1). Biological factors may include physiological processes or pharmacological side effects. Contributing lifestyle and environmental factors may include little physical activity, poor diet, and lack of access to quality preventive care, screening, and exercise facilities, which can lead to obesity and increased risk for diabetes. A recent analysis of death certificates in Minnesota found that individuals with SMI have an average life expectancy that is 24 years less than the general population(7) — a finding that is supported by a number of similar analyses (8,9,10,11). Increased risk for chronic health conditions like diabetes is one reason for the decreased life expectancy among individuals with SMI. As a provider, understanding diabetes and teaching individuals with SMI how to be an active participant in their treatment is essential for improving quality of life and helping people make progress in recovery.

What is Diabetes?

Glucose, commonly referred to as sugar, is an important source of energy for the body and the main source of energy for the brain. Insulin, a hormone secreted by the pancreas, helps us to regulate the amount of glucose in our bloodstream. Individuals who have diabetes either do not produce insulin (Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus) or have progressive insulin resistance (Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus), resulting in an inability to regulate glucose in the bloodstream (12).

Hyperglycemia

Hyperglycemia occurs when blood glucose is too high (13). A good way to remember the difference between hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia is to look at the prefixes. Hyper– means too high (think hyperactive) while hypo– means too low (think hypoactive). Hyperglycemia is characterized by a gradual onset of symptoms, though most persons with high blood glucose levels experience very few symptoms or have symptoms for many years without recognizing them (see Signs and Symptoms). It is important to help persons identify symptoms and to screen for diabetes on a regular basis as untreated hyperglycemia can lead to fatal complications, such as diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome (HHS), in the most severe and acute cases (12). Signs and symptoms of DKA include shortness of breath, fruity smelling breath, nausea and vomiting, and very dry mouth. Signs and symptoms of HHS include excessive thirst, dry mouth, increased urination, warm and dry skin, fever, confusion, vision loss, convulsions, and loss of consciousness. The most significant danger to persons with diabetes are the complications that follow after long periods of exposure to high blood glucose. These complications can include eye damage and blindness, kidney failure, heart attacks and strokes, infections, and even depression and dementia.

Signs and symptoms of hyperglycemia will vary per person, so it is necessary to know the person’s provider orders for seeking medical care in case of high blood glucose. In the event of hyperglycemia, the client should continue to take diabetes medications as ordered, check blood glucose frequently, drink fluids on at least an hourly basis, monitor for ketones in the urine, and contact the healthcare provider if indicated (12). The American Diabetes Association recommends exercising to lower blood glucose levels (14).

Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia occurs when blood glucose falls below the normal range. The normal range for a random blood glucose test is 70-110 mg/dL.12, 15 It is important to recognize signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia (Table 1) because untreated hypoglycemia can lead to seizure, loss of consciousness or death (13).

Once signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia have been recognized, the individual should check blood glucose with a glucometer. If blood glucose is < 70 mg/dL or if the client has a history of hypoglycemia attacks with unknown blood glucose level, start the “Rule of 15” (12).

Once blood glucose has returned to a level ≥ 70 mg/dL after a hypoglycemic attack, the client should eat a complex carbohydrate (i.e. vegetables, legumes, whole-grain bread, brown rice, whole-wheat pasta) to prevent another hypoglycemic attack (12).

Note: Do not use foods such as candy bars, cookies, milk, or ice cream to treat hypoglycemic attacks. The fat in these foods will slow absorption of the glucose (carbohydrates) and delay the response to treatment. Once the client has recovered from the attack, it is okay to include fat and protein as part of a meal with a complex carbohydrate (12).

Screening and Management

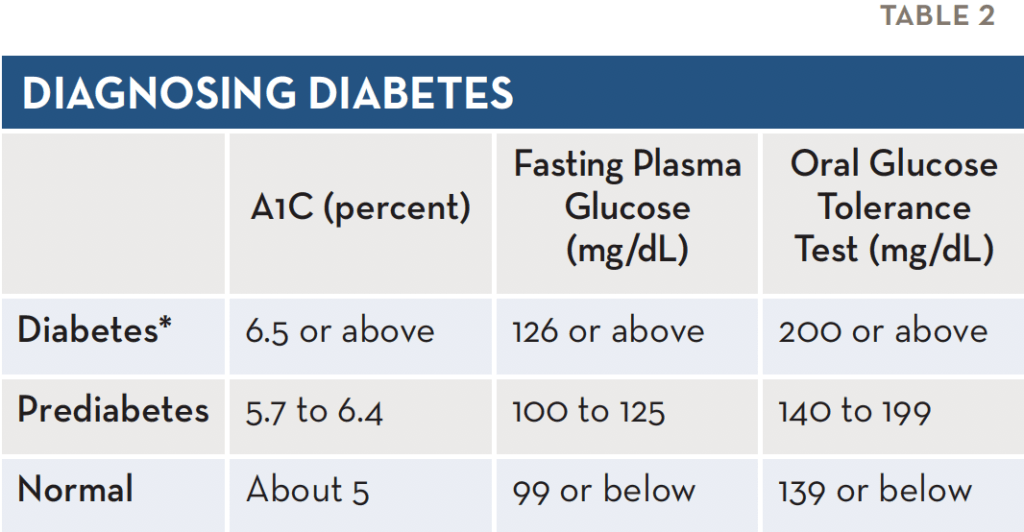

In the last five years, screening and management of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes have dramatically shifted thanks to a blood test called the Hemoglobin A1C (A1C). The A1C is a percentage of hemoglobin molecules in the blood with a glucose attached to them. Since hemoglobin molecules turnover in our blood stream periodically, this percent is correlated with a moving average of blood glucose over a three month period. For healthy adults, the typical A1C is 4.8-5.6%. Diabetes can be diagnosed with an A1C of 6.5% or greater, as shown in Table 2. When managing diabetes, the target A1C is 7% for most nonpregnant adults. Depending on the individual, more or less rigorous treatment goals may be required.

*Diabetes can also be diagnosed through a random plasma glucose test. With this test, diabetes is diagnosed when blood glucose is greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL and severe diabetes symptoms are present.

*Diabetes can also be diagnosed through a random plasma glucose test. With this test, diabetes is diagnosed when blood glucose is greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL and severe diabetes symptoms are present.

For many adults diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes, initial therapy does not require the use of insulin injections. Oral medication, diet, and lifestyle approaches can help achieve target A1C goals. For individuals in this initial treatment phase, daily glucose monitoring with finger sticks isn’t necessary and requiring it can dissuade many from proactively beginning to manage their diabetes. When people transition to insulin therapy or for Type 1 diabetics who require insulin, daily blood sugar monitoring is a necessary part of one’s managing diabetes. For more information regarding diabetes, visit the American Diabetes Association website at www.diabetes.org.

Resources are available upon request. Please email PracticeTransformation@umn.edu.

The Center for Practice Transformation is sponsored by funds from the Minnesota Department of Human Services Adult Mental Health Division and Alcohol and Drug Abuse Division.